The last voyage of submarine K-219

October 1986. Atlantic Ocean. U.S. Navy observation center specialists detected the echo of a powerful explosion. The coordinates pointed to a Soviet submarine patrolling in the area.

On September 4, 1986, the nuclear submarine K-219 departed from the Northern Fleet naval base in Gadzhiyevo for a combat patrol near the shores of a potential adversary—the western part of the Atlantic Ocean. It was the 13th patrol. By October 1, 1986, the strategic submarine K-219 was in the designated area in the Sargasso Sea, within missile range of the eastern coast of the United States.

The K-219 submarine, a Project 667A «Navaga» (Yankee-class by NATO classification), belonged to the family of nuclear-powered ballistic missile submarines with a range of up to 4600 km. A total of 34 units of various modifications were built in the USSR: 24 for the Northern Fleet and 10 for the Pacific Fleet. Each submarine was armed with 16 ballistic missiles, operating at maximum capacity. After returning from autonomous navigation, the submarine underwent a short repair before heading out again.

For submarine K-219, this voyage was supposed to be its last, as it was scheduled for decommissioning afterward. During a test run, it was discovered that there was a leak in the 6th missile shaft. However, the commission concluded that the submarine was ready for the patrol, attributing the issue to a faulty valve for draining water from the missile shaft. It was decided that the leak would be fixed at sea, as no one dared to take the nuclear submarine off combat duty due to such a minor malfunction. Explaining it to the CPSU Central Committee would be troublesome, and no one wanted problems.

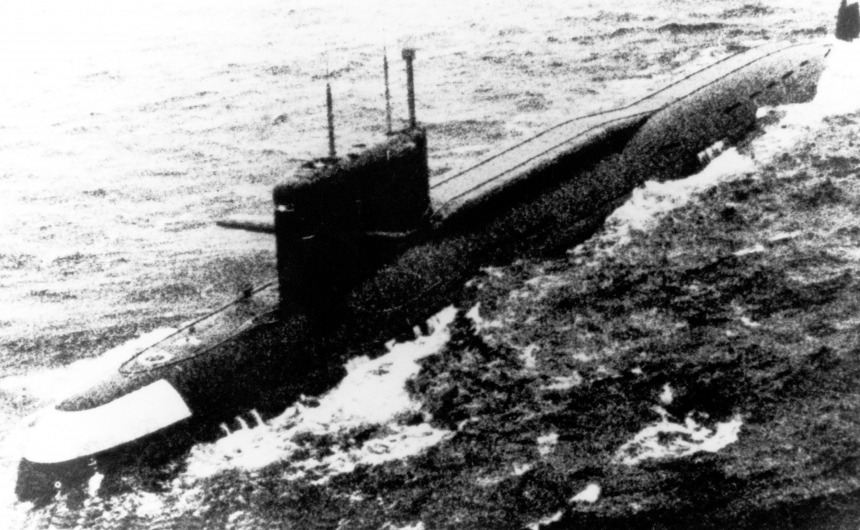

Yankee-class submarine

Yankee-class submarine

On October 3, 1986, water began to enter the 6th missile shaft through the ill-fated valve. The missile compartment crew independently drained the leaking water into the bilge without reporting to anyone. This continued until the irreversible process began.

Water gradually filled the 6th shaft. The missile inside compressed under immense pressure. The submariners activated pumps to pump out the water when the rocket casing straightened, causing a crack in the oxidizer tank. The oxidizer, nitrogen tetroxide, an aggressive and deadly toxic liquid, started leaking out. Smoke emerged from the missile shaft, and an emergency alarm was immediately declared. Events unfolded rapidly from there. At that moment, the second rocket tank, containing the propellant, ruptured due to the chemical reaction between the oxidizer and the fuel, resulting in a powerful explosion.

After the sudden explosion, the nuclear submarine plunged into the depths. Thanks to the well-practice automatic actions of the submariners, an emergency surfacing of the submarine was carried out. In just 2 minutes, the submarine resurfaced.

A few days later, an article appeared in the foreign press praising the incident with the Soviet submarine in the Atlantic Ocean and the actions of the crew. However, back home, the crew did not receive any commendation because the missile carrier had revealed itself near the shores of the United States, indicating a failed combat mission. But the submarine commander understood that dying in peacetime was pointless and foolish.

The explosion blew off the missile shaft hatch, and water began to enter the submarine. The strong mixture of water and oxidizer vapor, corroding metal, penetrated into the fourth compartment, bringing death to everyone. Those in the fourth compartment realized they were doomed. A few centimeters of metal became the boundary between life and death, sealed by a strict instruction. No one had the right to open the isolated compartment. However, the ship's commander had his perspective on the situation—after returning, the power of instructions would end, and he would have to face the mothers' eyes. So, he gave the order to evacuate people from the fourth compartment. As a result, 14 people were saved, but with severe poisonings. Unfortunately, three could not be saved.

Receiving a distress signal from the submarine in trouble, the central command center began to assess the situation. After the explosion, a nuclear warhead was lost—it was ejected by the blast. The behavior of the remaining 15 nuclear missiles was unknown. Despite the critical situation, sending combat ships to assist K-219 was not possible, as it would reveal their secrecy. Soviet merchant ships in the vicinity of the submarine accident received an encrypted message to go to the aid of those in distress.

The submarine K-219

The submarine K-219

Undoubtedly, the Americans had detected the submarine incident. The story of the K-219 submarine made headlines in many American newspapers. Photos of the surfaced submarine with smoke billowing from the destroyed missile shaft were published. Western newspapers started creating a buzz, discussing the dangers of liquid missile systems, especially considering the recent Chernobyl explosion six months earlier.

However, at that point, the Americans did not know and could not know that the submariners had not abandoned the damaged submarine. They were doing everything possible to prevent a nuclear catastrophe, despite the fact that the ship was turning into a hell.

A fire broke out in the fourth compartment as well. The fire spread to the fifth compartment through the electrical and ventilation systems. The main command center of the submarine, located in the third compartment, was cut off. The rest of the crew retreated from the fire toward the stern.

On behalf of Mikhail Gorbachev, the Soviet Ministry of Foreign Affairs took an unprecedented step during the long Cold War—sending a message to the U.S. president about the explosion of a Soviet submarine in the Atlantic openly and honestly. It was the first real evidence that «perestroika» was not just internal reforms but a radical turn in Soviet foreign policy. Ronald Reagan highly appreciated Mikhail Gorbachev's trust, marking the beginning of a new phase in relations between the two countries. However, there was one inaccuracy in the telegram—there was no threat of a nuclear catastrophe, but in reality, there was a threat. It was only due to the heroic actions and the sacrifice of the submariners that the reactors were shut down.

On the morning of October 4, 1986, five Soviet merchant ships, an American rescue ship, and an American submarine approached the accident site. American reconnaissance planes circled in the sky. The temperature in the compartments quickly rose, reaching 70 to 80 degrees Celsius. The submarine commander gave the order to abandon the underwater missile cruiser. A few minutes later, the submarine sank. Thus ended the 13th patrol of the nuclear submarine K-219 of the Northern Fleet of the Soviet Navy. It sank at 11:03 on October 6, 1986, in the Atlantic Ocean at a depth of 6 km. Four submariners perished, and 114 people survived.

Soviet citizens learned about the catastrophe from newspapers, but not on the front page; a short message was placed on the last page next to the weather report, stating that a fire had occurred on the submarine. Three people died, and the submarine could not be saved.

The rescued crew was initially taken to Cuba and then to Moscow, to the Navy Recreation Center «Gorki.» However, it was not for leisure, but for investigating the causes of the accident and for interrogations. At that time, Gorbachev's reforms were not enough to change stereotypes and recognize the actions of the submarine crew as heroic.

The heroism of Soviet sailors could only be appreciated by the Americans. The submariners themselves did not expect acknowledgment and only regretted one thing—that the experience of K-219 went in vain. If the right conclusions had been drawn, if the high commissions focused not on finding blame among the crew but on the reasons for the accident, the story of the submarine «Komsomolets» that occurred three years later might not have had such a tragic ending.

- Comments

en

en ru

ru uk

uk