Gato-class submarine

In the Gato class, the U.S. Navy had found a fully capable boat with the characteristics necessary to fight a war in the Pacific. In the wake of the Pearl Harbor attack, it was obvious that the only way to halt the rapid expansion of Japanese conquests would be with an unconventional strategy, and to their credit, Admirals King and Nimitz came up with exactly the right approach. They devised a dual strategy — containment around the edges and strikes deep into the heart of the Japanese Empire. The resources available were a small and terribly vulnerable force of aircraft carriers and three-dozen fleet submarines plus the nine old V-boats and a few more obsolescent S-class boats.

The containment was achieved by the aircraft carriers, which were deployed with courage and skill and turned back the Japanese at Coral Sea and decisively at Midway. The argument has been made with some persuasiveness that those reverses were inevitable, the result of serious overextension of Japanese resources, and that almost any American strategy would have eventually led to the same result, but the boldness of Nimitz and the skill of Fletcher and Spruance advanced the final decision by years and saved countless lives.

The deep strikes were achieved almost exclusively by American submarines. With the exception of the Doolittle raid of April 1942, American aircraft carriers were kept mainly on the periphery of the Japanese advance well into 1943. From the first days of the war, American submarines penetrated far into Japanese waters and exacted a steady toll of enemy shipping. At first that toll was smaller than it should have been for a number of reasons. One reason was the necessary learning curve as submarine commanders shook off the cautious habits of peacetime. Some never made the transition and were replaced; others adapted brilliantly. Another was the unreliability of torpedoes, which often failed to explode or ran erratically. Finally, there simply weren't enough boats to sustain a massive assault on enemy lifelines. Forty-odd boats, some ten or more years old, were nowhere near enough.

This last problem, at least, was well in hand. After the initial 1941 budget authorization of six boats of the new submarine Gato-class, events had conspired to dramatically increase that number. The fall of France to Nazi Germany was a wake-up call to U.S. legislators, and President Roosevelt finally had the money and authority to fill the available building slips with keels and more to follow when those were launched. On 20 May 1940, twenty-two more submarines were added to the initial six, followed by an additional forty-three on 16 August. These orders went out to the experienced Electric Boat Company (forty-one boats), Portsmouth Naval Shipyard (fourteen boats) and Mare Island Naval Shipyard (six boats), and to one newcomer to submarine construction, Manitowoc Shipbuilding Company (ten boats). When it was realized that Mare Island would have two free slips towards the end of this cycle, two more hulls were added to the order in April 1941. This brought the total number of the submarine Gato-class boats ordered before the attack on Pearl Harbor to seventy-three. Of this number, only one, Drum (SS 228), was in commission on 7 December 1941, but ten more had been launched and fully twenty-one more laid down before the Japanese attacked. After that the pace accelerated. There would soon be enough boats to do the job.

The seventy-three submarines Gato were assigned hull numbers SS 212 (USS Gato) through SS 284 (USS Tullibee). Unlike other navies that identified ships with pennant numbers that could be randomly changed, the Navy assigned permanent hull numbers, which used an alphabetic prefix indicating type, most often but not always two letters, and a number indicating sequence within type. Hull numbers were assigned in blocks to a particular builder when the boats were ordered. Hull numbers SS 212-227 comprised the original order from Electric Boat while SS 228-235 were ordered at the same time from Portsmouth. These numbers did not reflect in any way die order in which boats were started or completed. It wasn't unusual that Drum (SS 228) was started and completed before the submarine Gato (SS 212). The numbers assigned to boats that were cancelled generally weren't reassigned. Even though the highest numbered the submarine Gato actually completed was Grenadier (SS 525), numerous boats in the final wartime orders were cancelled, some with lower hull numbers and others with numbers all the way up to SS 562.

Thus the first postwar attack submarines built by the Navy were the six boats of the 7cmg-class that started with hull number SS 563. If a boat changed role, she might have her hull number prefix changed, but not the sequence number itself. Thus, when Cavalla (SS 244) was rebuilt as a hunter-killer boat in 1952, she emerged as SSK 244. The Gatos differed from the preceding Tambors only in minor details. The submarine Gatos were 51 tons heavier and 4 feet 6 in (1.4 m) longer. The extra length went into the planned installation of larger, more powerful diesels and the addition of a watertight bulkhead between the two engine rooms. However, the new diesels weren't ready in lime to be installed in any of the first-generation Gatos, and the engines actually installed were in fact the same size as those in the Tambors. This had no effect on the boats speed, since the diesel-electric propulsion scheme didn't directly connect the diesels to the propeller shafts. The critical factor was the electric motors, which were also the same size in Gatos as in the Tambors. However, the extra length of the submarines Gatos made the hull form slightly more efficient; giving them a half-knot more speed on the surface (21 knots). That and improved, more powerful batteries also gave them a quarter-knot more submerged speed (9 knots). This greater efficiency and the increased length, which allowed fuel oil capacity to rise to 94,000 gallons (355,8291), increased the range to 12,000 nautical miles at 10 knots. As a result of testing Tambor with live depth charges, internal finings in the submarine Gato-class were improved, and the test depth was increased by 50 feet (15.24 m) to 300 feet (91.44 m). The calculated crush depth remained the same at 500 feet (152.4 m). The test depth was the depth to which a boat would be tested as part of her acceptance trials. She was expected to reach that depth without any leaks or pressure-related failures. In wartime, the test depth was regularly exceeded by captains trying to evade depth charging. The crush depth is the theoretical limit below which the hull would collapse.

The submarine Gato class

The submarine Gato class

The interior of a Gato-class submarine was divided into nine watertight compartments:

Forward Torpedo Room

This was the site of the six forward torpedo tubes, four of which were visible above the deck plates. The other two could only be reached by removing the deck plates. At the start of a patrol, there would be one torpedo in each tube, one reload each for the two lower tubes stored below the deck plates, and two reloads for each of the four upper tubes — a total of sixteen torpedoes. The sonar gear was raised and lowered and or rotated from this compartment, as was the pitometer log. Fourteen bunks for crewmen were also found in this compartment.

Forward Battery Compartment

Half of the boat's 252 battery cells were located below the deck plating of this compartment. Above this deck was the site of the wardroom where the officers ate, the pantry where their food was plated, and the three compartments where the officers berthed. One compartment was for three junior officers. The executive officer and first lieutenant shared another compartment. The captain had his own compartment, the only private space on the boat. The five mast senior chief petty officers shared a fourth compartment. If, as was often the case, there were more than the nominal complement of six officers — some boats went on patrol with as many as ten officers-this space got rather crowded. This compartment also contained the yeoman's office, where reports were prepared and the log maintained, and the officers' shower and head.

Control Room

This was the center of the boat, from which she was steered and her depth was controlled. The Hull Opening Indicator Panel, known as the 'Christmas Tree'. It got that name because there was a red and green light for every opening in the pressure hull, green indicating the opening was closed. Flooding or blowing of all tanks was controlled from this compartment. Below this room was the pump room, where most of the boat's pumps and compressors were located. The radio shack was at the aft end of this compartment.

Conning Tower

This was a separate, relatively tiny cylindrical compartment located above the control room and housed within the boat's external tower structure. Both of the boat's periscopes were operated from the conning tower. The first submarine Gato had a Type 2 attack or 'needle' periscope and a Type 3 search periscope with a broader angle of view. Starting in 1944, a Type 4 'night' periscope replaced the Type 3. The Type 4 had a larger head to admit more light, a shorter tube so that less light was dispersed, and incorporated the ST range-only radar to aid in making submerged night attacks. The Torpedo Data Computer was on the port bulkhead aft. The displays for the surface search radars and active sonar were located here, as was a secondary steering position. Repeaters for most of the primary gauges found in the control room were located here as well. When a submerged attack was being made, this was a very crowded space, as the captain, executive officer; one or two operators, one or two radar/sonar operators, and a talker were all stationed here.

The Gato cass

The Gato cass

After Battery Compartment

The remaining 126 battery cells and the magazine were located here beneath the deck plating, as was the main pantry, freezer, and refrigerated food storage. Above this deck was located the medical locker, the crew's mess, the galley where all food for officers and men was prepared, and thirty-six bunks. The crew's showers and head were at the aft end of this compartment, as was the boat's washing machine and the tiny storage lockers where the crew could store valuables. This is the largest of the boat's compartments.

Forward and After Engine Rooms

These two compartments were basically identical. Each contained two of the four main diesel engines. Each diesel was connected to a 1,100 kilowatt electrical generator used to charge batteries and/or drive the electric motors as needed. The diesel engines found in Gato-class boats were 1,600 bhp two-cycle units made by General Motors or Fairbanks-Morse. The latter were license-built Junkers Jumo engines. The GM engine was a V-16 Model 16-278 or 16-278A, each with two banks of eight cylinders, which ran at 750 rpm. The F-M engine was a Model 38D, available in nine-and ten-cylinder versions, both opposed-piston designs running at 720 rpm.

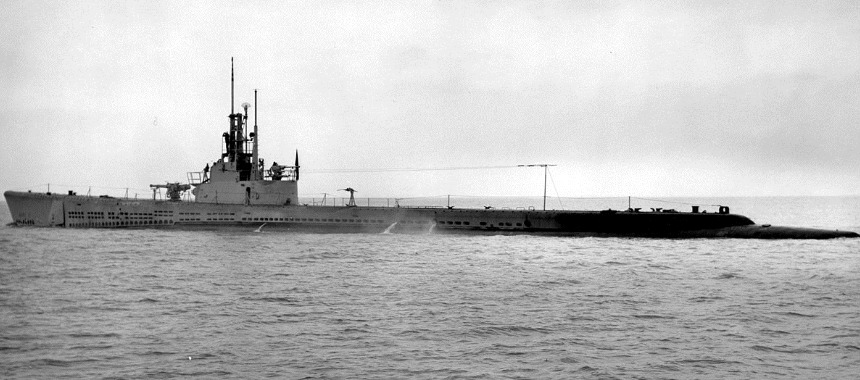

Harder in the Mare Island

Harder in the Mare Island

Maneuvering/Motor Room

The four electric motors of 1,350 hp each and the two sets of reduction gears that connected them to the propeller shafts were located below the decking. The switch panels that controlled the motors and gearboxes were located above the deck in the maneuvering room. The electric motors ran most efficiently at a constant, high speed. The speed of the boat was controlled by changing the gearing in the Westinghouse gearboxes, in much the same way that an automotive transmission functions.

After Torpedo Room

This compartment housed the remaining four torpedo tubes and eight torpedoes, four in the tubes and four reloads on skids, one for each tube. It also contained fifteen more bunks for crew berths and the bosun's tool locker. That totaled seventy bunks, not counting officers' berths, or one bunk for each of the nominal wartime enlisted crew, but several factors contributed to cause hot 'bunking,' in which three men shared two bunks. One factor was that the crew was often larger than expected. By war's end, the enlisted complement often exceeded eighty men. Also, some bunks in the torpedo rooms couldn't be lowered until some of the reloads had been moved into the tubes and as the war progressed and targets became fewer, some boats went an entire patrol without firing off a lull load of torpedoes.

The Gatos were double-hulled boats, meaning that die pressure hull was surrounded by a second non-watertight hull containing the boat's various ballast, trim, and fuel tanks. The central section of the pressure hull was an externally-framed cylindrical structure constructed of 14.3 mm, 12.5 kg untreated steel. The two end compartments were truncated conical sections, and the conning tower was a smaller cylinder fitted on top of the main pressure hull above the control room. The maximum diameter of the pressure hull was 16 feet (4.9 m).

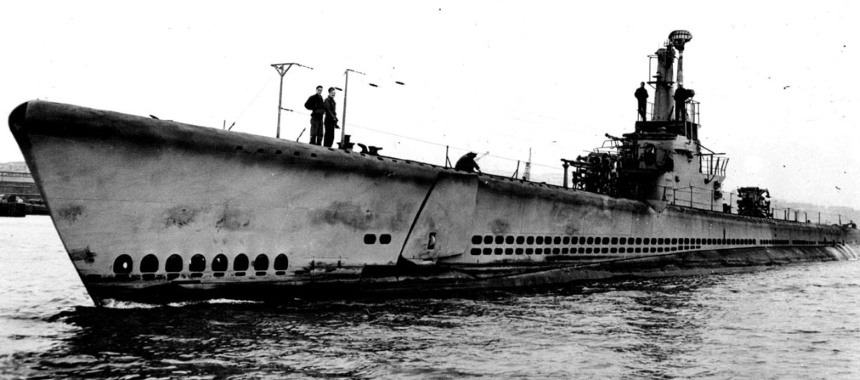

USS Gato

USS Gato

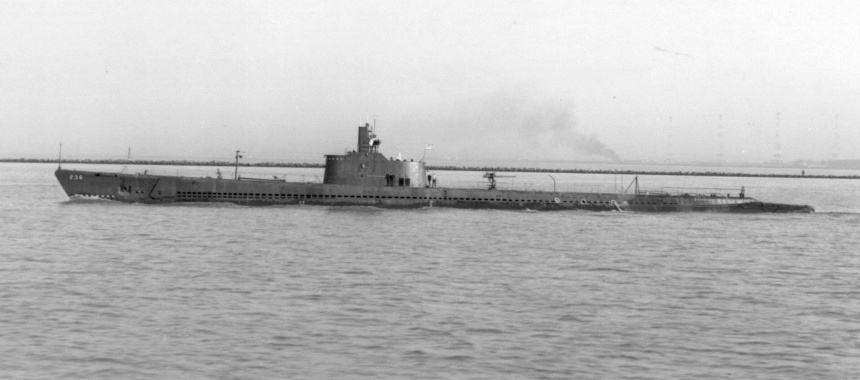

On top of the outer hull was an external superstructure. This included the deck casing that gave the boat a shape that allowed high surface speed. Forward, the deck casing housed the boat's anchor and capstan, the forward dive planes, and a buoyancy tank. The deck was strengthened forward and aft of the bridge to allow the installation of two 3-inch, 76.2 mm deck guns, though in practice only one was ever carried. This deck casing trapped air as the boat submerged and accounted in part for the relative slowness with which American submarines dived. This was counteracted in part by the addition of limber holes in the side of the superstructure. The conning tower was enclosed in an external tower or fairwater structure that included an enclosed bridge with a conning station. An open area aft, known to the crew as the 'cigarette deck' for obvious reasons, had a pintle mount for a Browning. There were minor differences in appearance between the boats built by Electric Boat and those built at the government-run navy yards. The most obvious initial difference was in the pattern of limber holes, which were more numerous and extended further aft from the bow in government-built boats. As the war progressed, the tower structure of new and refitted boats was cut down and modified to carry more armament and antennae, and the number and pattern of limber holes in the superstructure varied greatly. It is safe to say that, while boats from the three sub-classes of Gatos were often indistinguishable, no two boats were absolutely identical in appearance.

All seventy-three submarines Gato saw combat. Of the ten most successful American submarines in terms of tonnage sunk, eight were from this submarine class. Nineteen were lost during the war.

- Comments

en

en ru

ru uk

uk